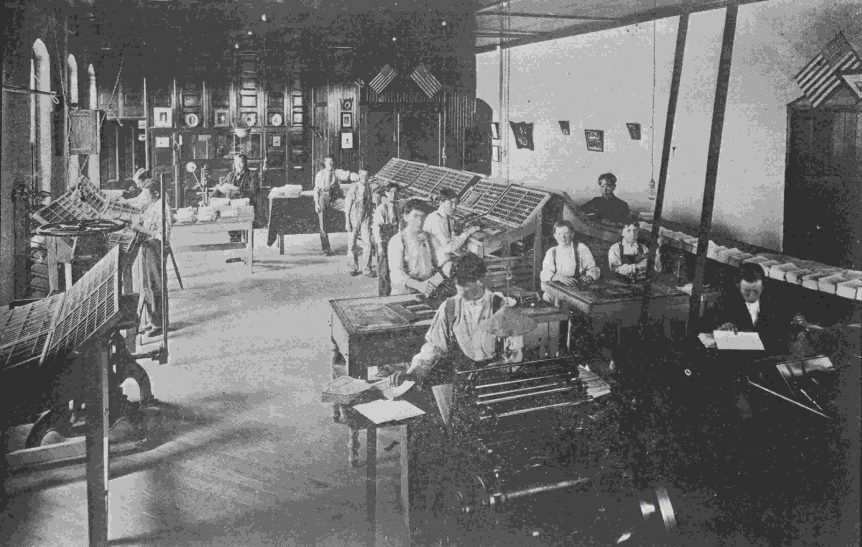

George Woods, a cadet at the Whittier State School, was a good kid. How do we know anything about George? The boys and girls attending the Whittier State School (WSS) published a monthly magazine called, appropriately, The Whittier Boys and Girls Magazine. It was both written and printed at the school by the boys in the printing shop. The girls submitted articles, stories, essays and poems to the Magazine, but they were not involved in editing, lay-up, or printing as the boys were. The California State Archives in Sacramento have a good collection of the WSS publications. Staff and volunteers of the Whittier Historical Society photographed every page of every available issue when we visited the Archives a year ago. As we were reading the Magazines, there were certain cadets who seemed to stand out – they had a certain spark of personality. That brings us back to George.

“With a face as black as a lump of coal and crooked legs, little George Woods, aged 10, was sent to Whittier from San Francisco several years ago. He was first found by Sister Julia on the door steps, taken in and cared for until he was ten years old. Barring his bow-legs, George had a well developed body and mind but the good sister began to loose her grip upon the lad when he ran away and mingled with the San Francisco street arabs, and so he was turned over to the State School. Beneath his ebony-hued skin lies rare artistic talent, for George can paint and sketch in a way that would do credit to an adult who had received years of training, yet he never had a lesson” (April 1904).

In fact, George was sent to Whittier in June 1899; he was the 1,351th cadet enrolled in the Whittier State School. He was introduced in the Company B (boys 13 and under) notes as follows, “’White folks, is yer lookin’ at me?’ Whenever you see something black rolling around on B company’s ground it will either be Bart Wade’s dog ‘Billy,’ or George W. Wood, Esq., or both. They wallow and roll together so much that we can’t tell t’other from which. George has no use for hat or shoes, and his leg is set so near the middle of his foot, that it is difficult to tell which way he is going to walk. We wouldn’t take six bits for our interest in that little black man” (August 1899).

Company B baseball team in 1904.

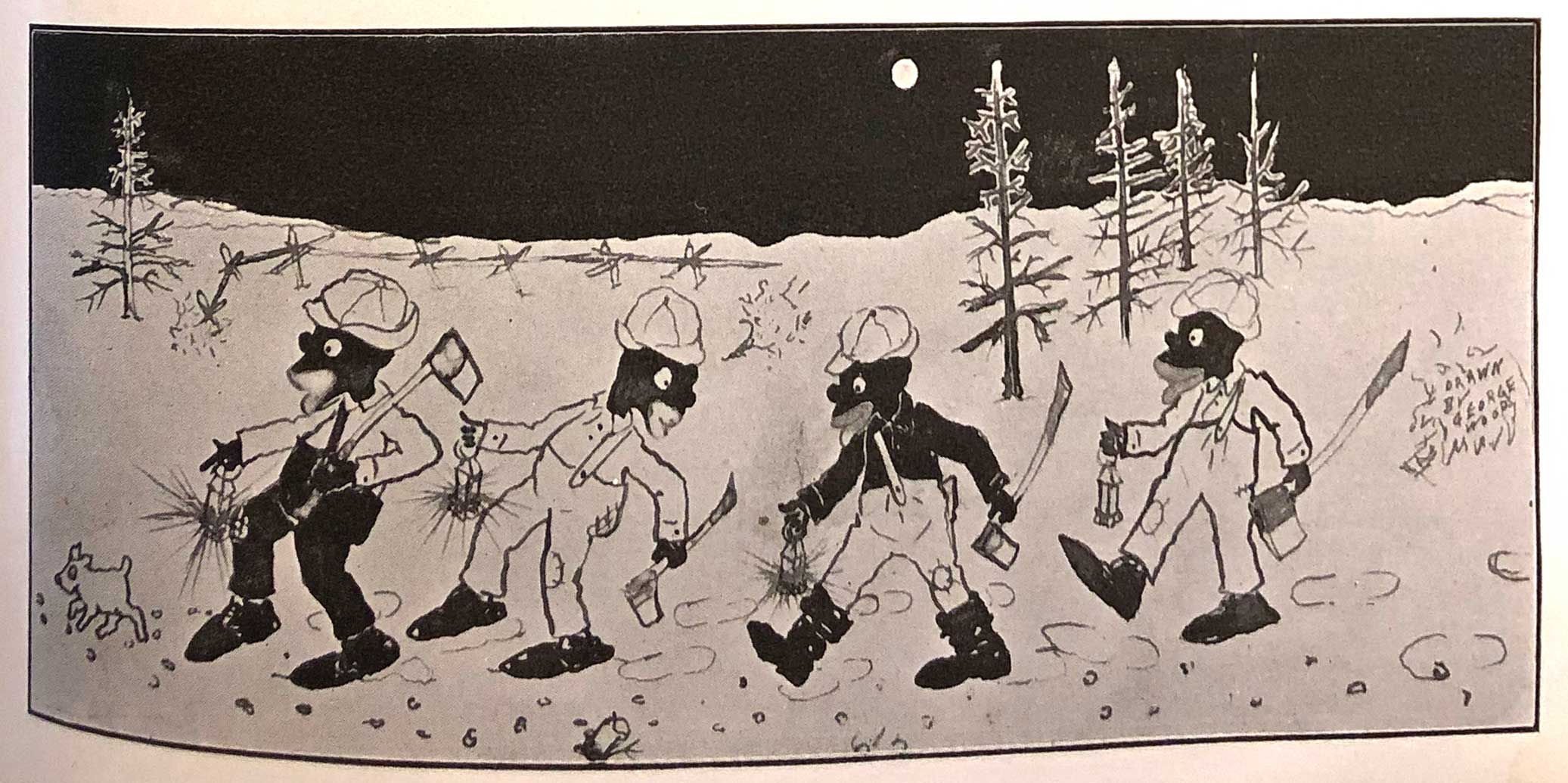

Because the younger boys did not attend training in trades, we didn’t hear much about George until he was 14 years old. His artistic skill was often commented upon and admired. “Cadet George Woods has been drawing a glass for the company’s magic lantern [an early type of image projector], and also for Mr. Wade. He is a genius, and will be heard from some day” (February 1904). In the December 1904 issue, George wrote a story titled “Little Rastus’ Christmas Eve” to go along with several cartoons he had drawn.

This may have gotten the attention of the printing instructor, because the very next month George was invited to join the boys in the printing shop. “George Woods, aged 14 years, is now a member of the printing force, and it is the opinion of all that he will make a success of the trade” (January 1905). As the newest member of the printing shop, George was assigned the apprentice job of “printer’s devil” – and it seemed to fit his personality. “George Woods, who occupies the exalted position of his Satanic Majesty to the printing force, has portrayed one of his race posing with an opossum. He said he would tell the Magazine readers all about it, but owing to the ‘pressing’ demands of his trade, has failed to make good” (April 1905).

George finally joined the ranks of the big boys when he moved from the Company B cottage to Company E in the main building, or “castle”, in mid-1905. He also moved to school room number 2 which was fifth grade. The highest grade level in the Whittier State School during that time period was eighth grade. George was never listed as one of the high achievers in school, but his writing for the Magazine showed that he had more than a passable grip on the English language.

He reports on Company E’s trip to Catalina in 1905 as follows, “Captain Lynch and Officer Crane took the boys for a boat ride which was greatly enjoyed. We also made a trip to Black Jack [Mountain], but failed to reach the top. When we got about half way hunger began to lessen our ambitious desires of going to the summit, and upon a deciding vote as to whether we would go on and do without dinner, or give up Black Jack and return for dinner, the thoughts of sitting down to a well loaded table of good things to eat turned us on the home march for that day at any rate. Your humble reporter won the sack race in the Fourth of July events, and received a fine catcher’s glove for his furnishing sport to the spectators” (July 1905).

In the fall of 1905, it was noted in the Printing Shop report that “George Woods, who is still holding his reputation as a pen and ink artist, hopes to be able to make some little booklets containing his sketches, which will be sold and from the proceeds he hopes to lay by a few dollars for a rainy day” (Oct. 1905). It’s interesting that boys were allowed to earn money while at the Whittier State School. Most boys who were granted this privilege earned money by farming-related tasks such as harvesting walnuts and citrus. George, of course, made money with his art. One woman who was visiting the printing shop bought a pen and ink sketch from George. George must have impressed her mightily because she later wrote to him, “It is very kind of you to think of painting me a picture, and I shall value it highly, for some time in the great future you hope to become famous in your line, and then I can point to your picture and say: ‘George Woods worked out his own good name by sound and hard work. He has courage, ability and good sense. He was generous, manly and obedient, and has earned an honored name’” (April 1906).

George Woods was beginning to leave his childhood behind. It was reported in the Nov. 1905 issue that George had been promoted from printers’ devil to a regular member of the printing shop and that he had been transferred to Company G. There is one additional note in the November issue that states that Woods was among the boys in Company G who received visits from relatives. This is perplexing because it was thought that George had been abandoned as an infant. Was this a mistake, or had a relative of George’s stepped forward? A few months later, it was recorded that “Cadet George Woods is working in Whittier because he ‘needs the money’” (Jan. 1906).

George Woods was released from the Whittier State School on May 25, 1906; he was a cadet for almost seven full years. Where did he go and what did he do? Did he become a successful artist? Unfortunately, we don’t currently have any information regarding George’s post reform school life. We will probably never know, but I like to think that George lived a long and happy life.

Author: Tracy Wittman

This post originally appeared in the Whittier Museum Gazette, Feb. 2020