You never know what someone is going to bring to the Whittier Museum. Majority of the time it’s copies of Whittier High yearbooks or Whittier Daily newspapers; but every so often it’s something very unexpected.

At the beginning of August, during the sixth month of our temporary closure, I was contacted by Sarah Hall, a Whittier resident, who was inquiring if the museum would be interested in accepting a homemade telescope built by a former Whittier resident, Paul Nemecek. Sarah’s father, Mike Pavelski, had acquired Nemecek’s telescope years ago as a keepsake from Nemecek’s family, but was now unable to keep it. A homemade telescope sounded like a wonderful item to be added to our collection relating to technologies and clubs in Whittier.

Regrettably, I was not familiar with the name Nemecek from any of our files, but was hoping to find out more from his daughter, Corrie Garland. Several days went by till I received a visit from Corrie. When meeting, she expressed surprise that Whittier had a museum, unfortunately a sentiment we often hear! Corrie met Mike Pavelski and they discussed the best place to house her father’s telescope: the Whittier Museum.

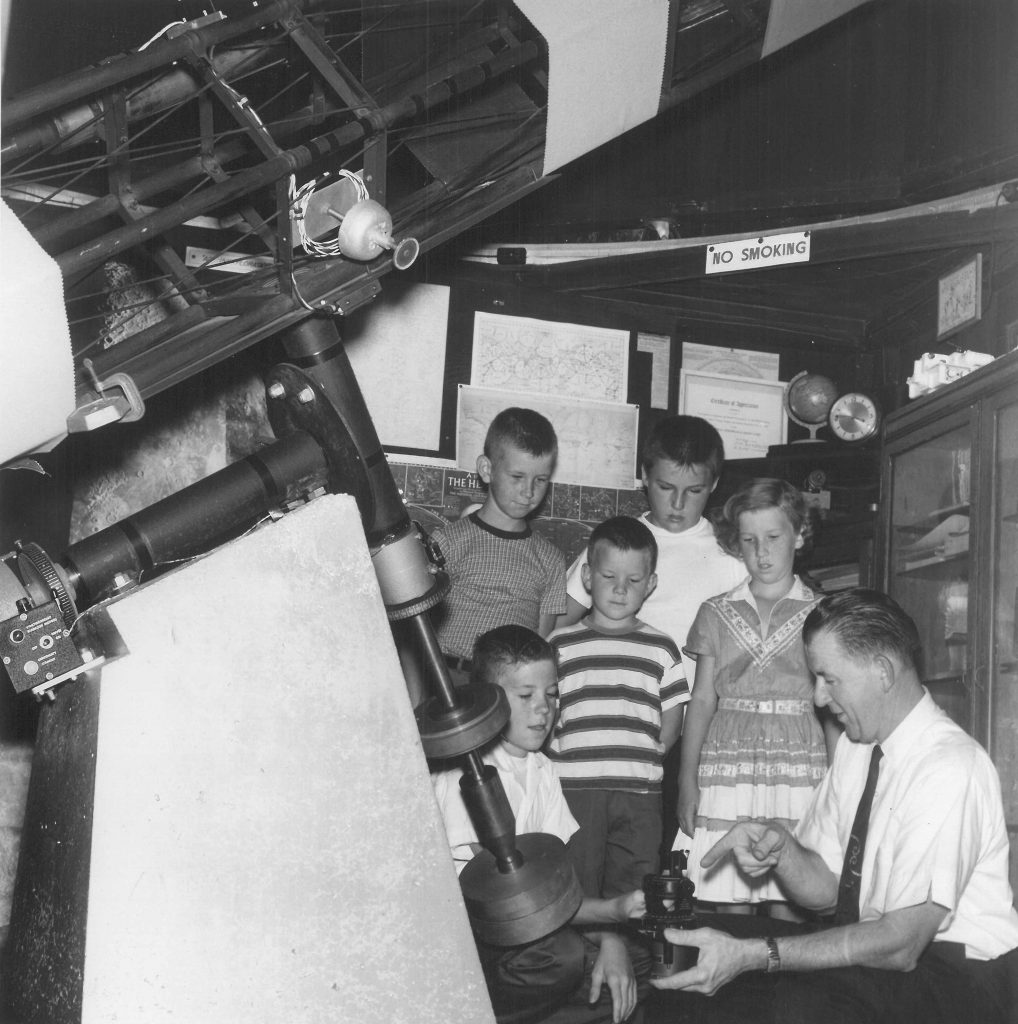

Up until this point, I had not yet seen a photo of the telescope and had been under the impression, from how both parties talked so easily about moving it, that it was not that large. When Corrie visited the Museum, she brought along an album of photographs and newspaper clippings featuring her father and his telescope. When opening the album to see this full sized astronomer’s telescope, I was in shock! It was absolutely beautiful and huge! Despite the confusion, I was still determined that the Museum should have this telescope, especially after hearing so much about its owner, Paul Nemecek and his connection to one of the most important events in space history.

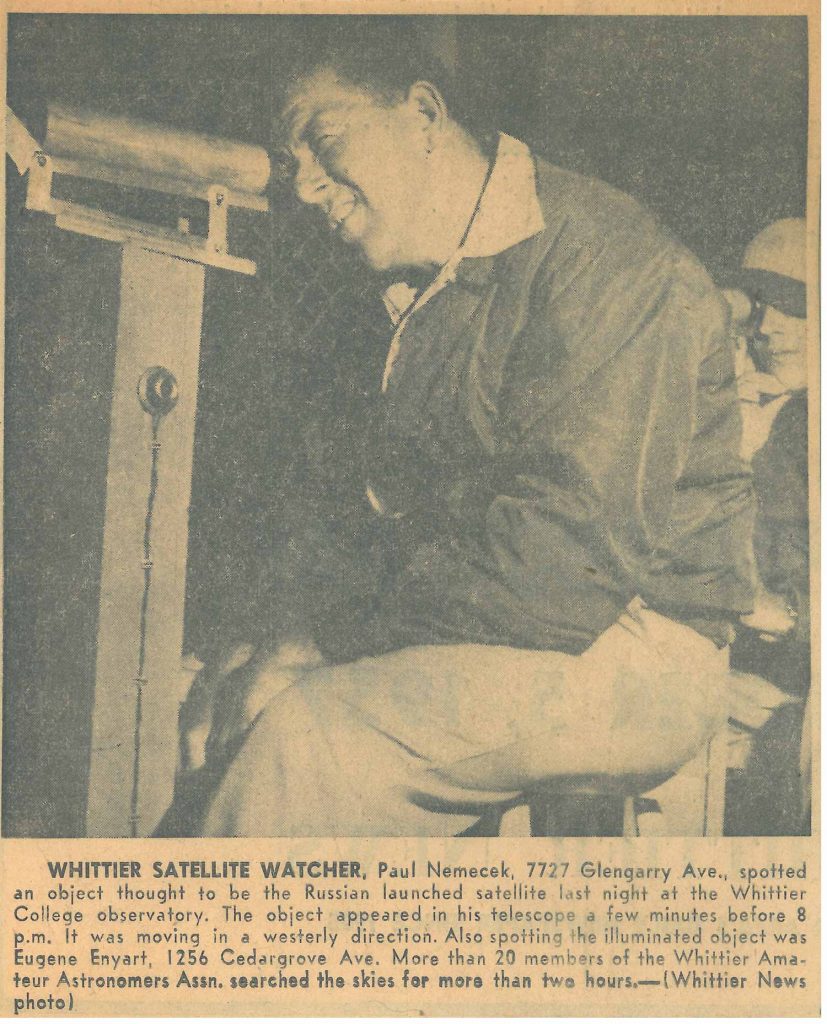

Sixty-three years ago on October 5th, 1957, a front page headline of The Whittier News evening edition blared “Local Observers See Red Satellite.” The first sentence read “An unidentified object thought to be the Russian-launched satellite streaked across Whittier early last night.”

The Russian satellite was Sputnik-1, launched the previous day from the Soviet Union. Sputnik-1 was the first artificial satellite to be successfully launched into orbit. This event also launched the start of the space race between the United States and Soviet Union. The United States wouldn’t launch their own satellite until May the following year; Russia successfully launched a second Sputnik the month after the first.

Readers should remember that this was the Cold War era, a period beginning after World War II till the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union. This period was a hostile political war between the United States and Soviet Russia, each one preparing for a catastrophic outcome, each one launching a massive build-up in technological advancements and arms manufacturing. Both nations reinforced fear of one another’s political ideologies.

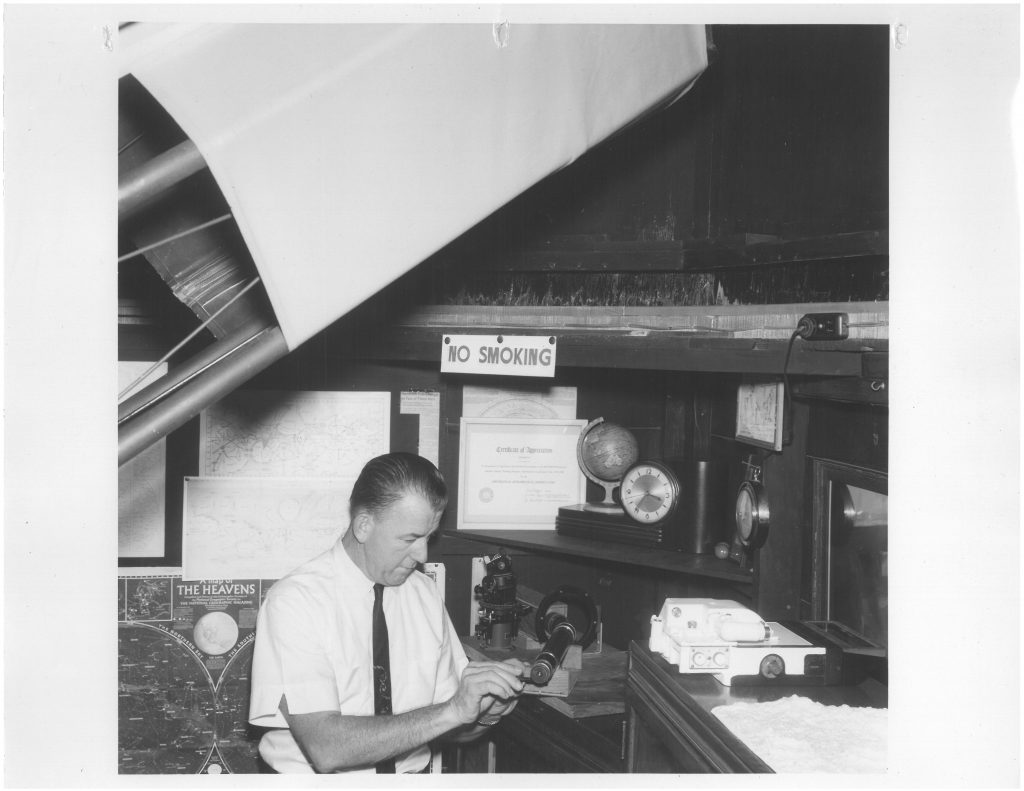

Paul Nemecek and his friend Eugene Enyart were the first men to see Sputnik-1 on the west coast. “The object, they said, passed through their field of vision and reflected about the same amount of light as does a star. It was not visible to the naked eye.” (The Whittier News, Oct. 5, 1957) The two men were part of a team of observers from the Whittier Amateur Astronomers Association who were using low-power, wide-angle telescopes at the Whittier College Observatory. At the time, the Whittier College Observatory was the only operating satellite observing group in Southern California and had been requested by the Smithsonian Astrophysics Observatory to help observe Sputnik-1.

When the Sputnik-1 was launched, the Whittier Astronomers immediately took their places as part of Operation Moonwatch, a team project of observers around the world who “would track, time and record satellite passes over their location and feed this data back to the computation center at Cambridge, Massachusetts” (Citizen Science, Old-School Style: The True Tale of Operation Moonwatch, UniverseToday.com). Nemecek and Enyart were the only two from the Whittier association to see Sputnik-1.

Nemecek worked for North American Aviation in Downey and Anaheim as a quality engineer; the company later became North American Rockwell. Rockwell was the NASA contractor for the Apollo Program Command and Service Modules. Like many children of aerospace employees, Corrie fondly remembers watching the Apollo 11 moon landing with her father and the pride she felt in his contribution.

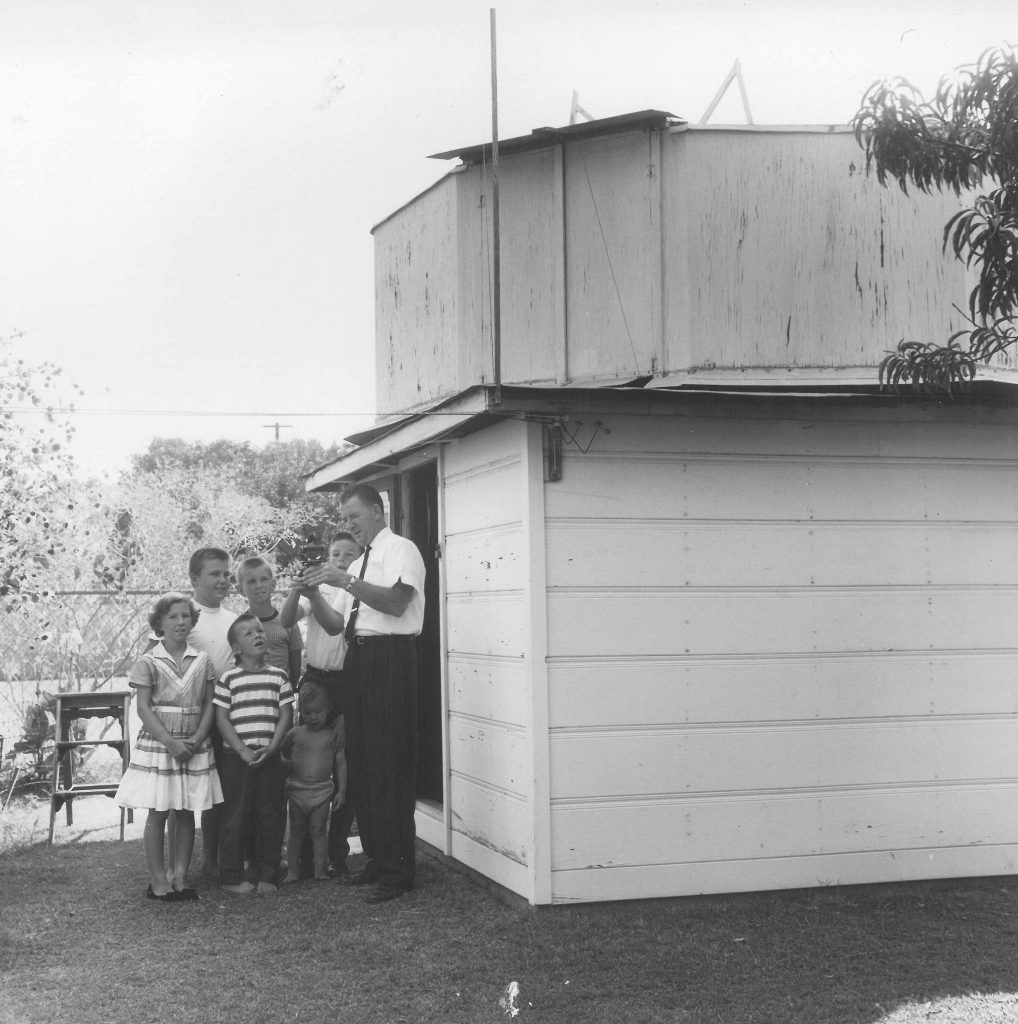

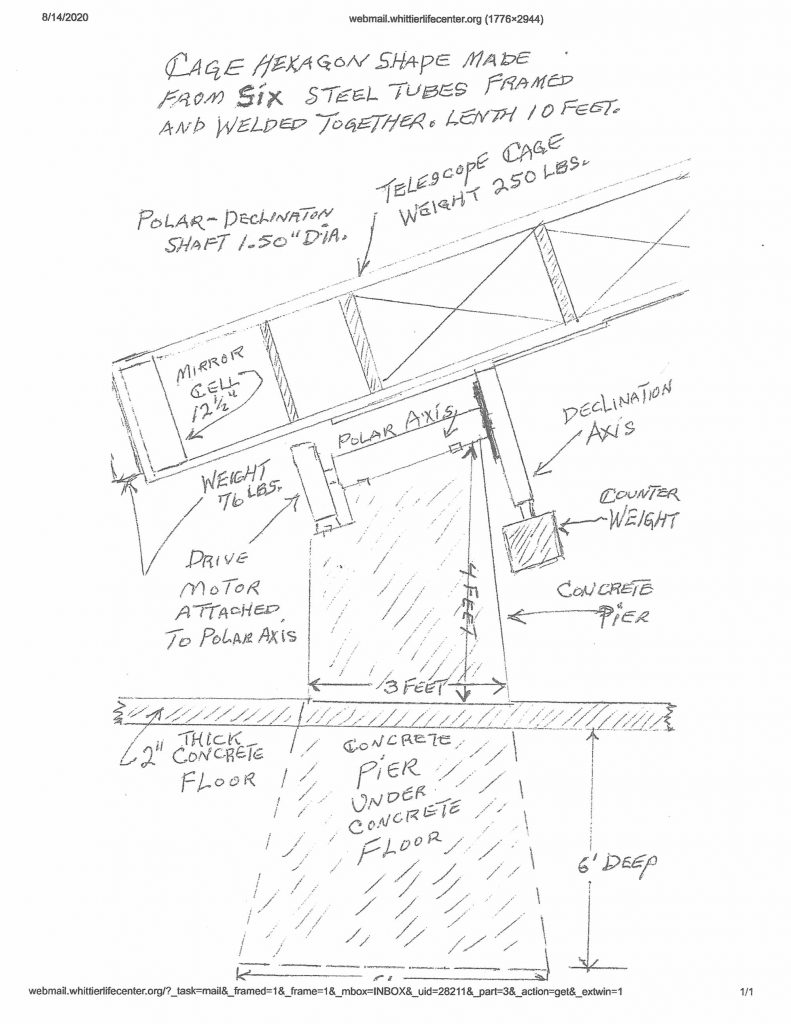

Paul Nemecek and his wife, Marguerite, moved into their home on Glengarry in 1952. He transformed the backyard shed into his home observatory, then constructed his telescope. He even had an intercom installed to communicate with the house; it was often used to remind him dinner was waiting.

Corrie described her father as a “detailed and thorough man,” as you would expect of an aeronautics quality engineer. Her favorite memory was climbing the high ladder inside the observatory in order to look up at the moon and listening to her father’s stories about the heavens.

Corrie’s motivation to preserve the telescope was influenced by the sudden awareness that her father was mentioned in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Nemecek and Enyart are featured in the Sputnik-1 exhibit where a copy of the Los Angeles Times recounts their story from The Whittier News.

Unfortunately with Nemecek’s passing in the late 1970s, his telescope went unused and fell into disrepair. It’s our hope to reassemble the telescope with the help of local astronomers and have it on display in our Red Car Room. We are seeking anyone one or groups interested in contributing to this restoration project and construction of this new exhibit.

Author: Nicholas Edmeier

This post is adapted from an article that originally appeared in the Whittier Museum Gazette, October 2020