Born and educated in Blue Earth, Minnesota, Mabel George Haig has been recognized as one of Whittier’s important artists and community leaders.

She first came to Whittier at the age of ten with her mother in 1894, seven years after Whittier’s establishment by the Quakers, to visit her grandparents, Hiram and Nancy Mendenhall. Mabel’s grandparents lived in a clapboard farmhouse on Mendenhall Ranch in East Whittier. East Whittier Middle School now stands on land that was part of Mendenhall Ranch.

Mabel George returned to visit Whittier multiple times before marrying Myron Haig and then finally moving to Whittier in 1914. The newlywed couple built their home on Hadley Street in Whittier in 1919.

Both Myron and Mabel were beloved community leaders. Myron Haig served as secretary of Whittier’s Chamber of Commerce from 1915 until 1925.

Mabel George Haig was an artist and a writer. She was very involved with the Whittier Women’s Club, and in 1934, the major co-founder of the Whittier Art Association & Gallery. She was a member of the California Water Color Society from 1923 to 1933, Laguna Beach Art Association, American Association of University Women (AAUW), and appears in the American Art Annual 1925 to 1933, California Arts & Architecture, 1932,Who’s Who in American Art, 1936-1941, and Who’s Who in California, 1942. Mabel died on Oct. 27, 1977 in Whittier.

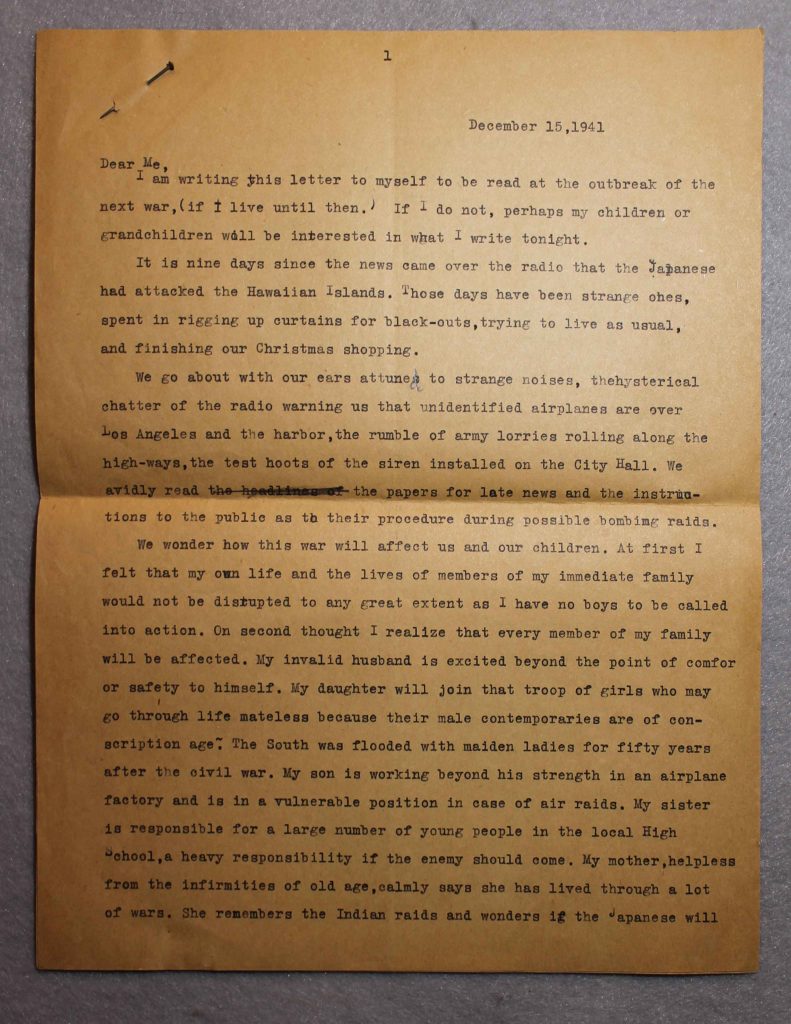

Below is a transcription of a typed letter by Mabel George Haig. She wrote the letter shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The letter was provided by Vicki Schramm, past president of the Whittier Art Association, with the permission of Mabel’s family.

December 15, 1941

Dear Me,

I am writing this letter to myself to be read at the outbreak of the next war, (if I live until then.) If I do not, perhaps my children or grandchildren will be interested in what I write tonight.

It is nine days since the news came over the radio that the Japanese had attacked the Hawaiian Islands. Those days have been strange ones, spent in rigging up curtains for black-outs, trying to live as usual, and finishing our Christmas shopping.

We go about with our ears attuned to strange noises, the hysterical chatter of the radio warning us that the unidentified airplanes are over Los Angeles and the harbor, the rumble of army lorries rolling along the high-ways, the test hoots of the siren installed on the City Hall. We avidly read the headlines of the papers for late news and the instructions to the public as to their procedure during possible bombing raids.

We wonder how this war will affect us and our children. At first I felt that my own life and the lives of members of my immediate family would not be disrupted to any great extent as I have no boys to be called into action. On second thought I realize that every member of my family will be affected. My invalid husband is excited beyond the point of comfort or safety of himself. My daughter will join that troop of girls who may go through life mateless because their male contemporaries are of conscription age. The South was flooded with maiden ladies for fifty years after the civil war. My son is working beyond his strength in an airplane factory and is in a vulnerable position in case of air raids. My sister is responsible for a large number of young people in the local High School, a heavy responsibility if the enemy should come. My mother, helpless from the infirmities of old age, calmly says she has lived through a lot of wars. She remembers the Indian raids and wonders if the Japanese will burn her house.

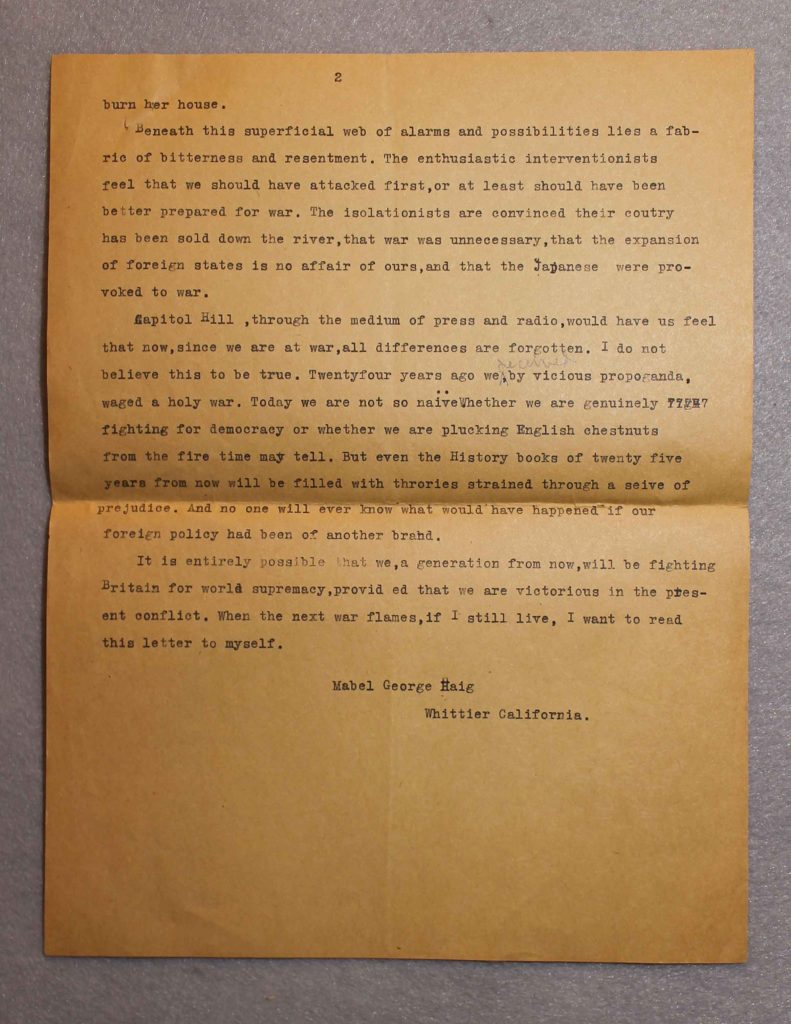

Beneath this superficial web of alarms and possibilities lies a fabric of bitterness and resentment. The enthusiastic interventionists feel that we should have attacked first, or at least should have been better prepared for war. The isolationists are convinced their country has been sold down the river, that war was unnecessary, that the expansion of foreign states is no affair of ours, and that the Japanese were provoked to war.

Capitol Hill, through the medium of press and radio, would have us feel that now, since we are at war, all differences are forgotten. I do not believe this to be true. Twenty four years ago we, deceived by vicious propaganda, waged a holy war. Today we are not so naïve. Whether we are genuinely fighting for democracy or whether we are plucking English chestnuts from the fire time may tell. But even the History books of twenty five years from now will be filled with theories strained through a sieve of prejudice. And no one will ever know what would have happened if our foreign policy had been of another brand.

It is entirely possible that we, a generation from now, will be fighting Britain for world supremacy, provided that we are victorious in the present conflict. When the next war flames, if I still live, I want to read this letter to myself.

Mabel George Haig

Whittier, California