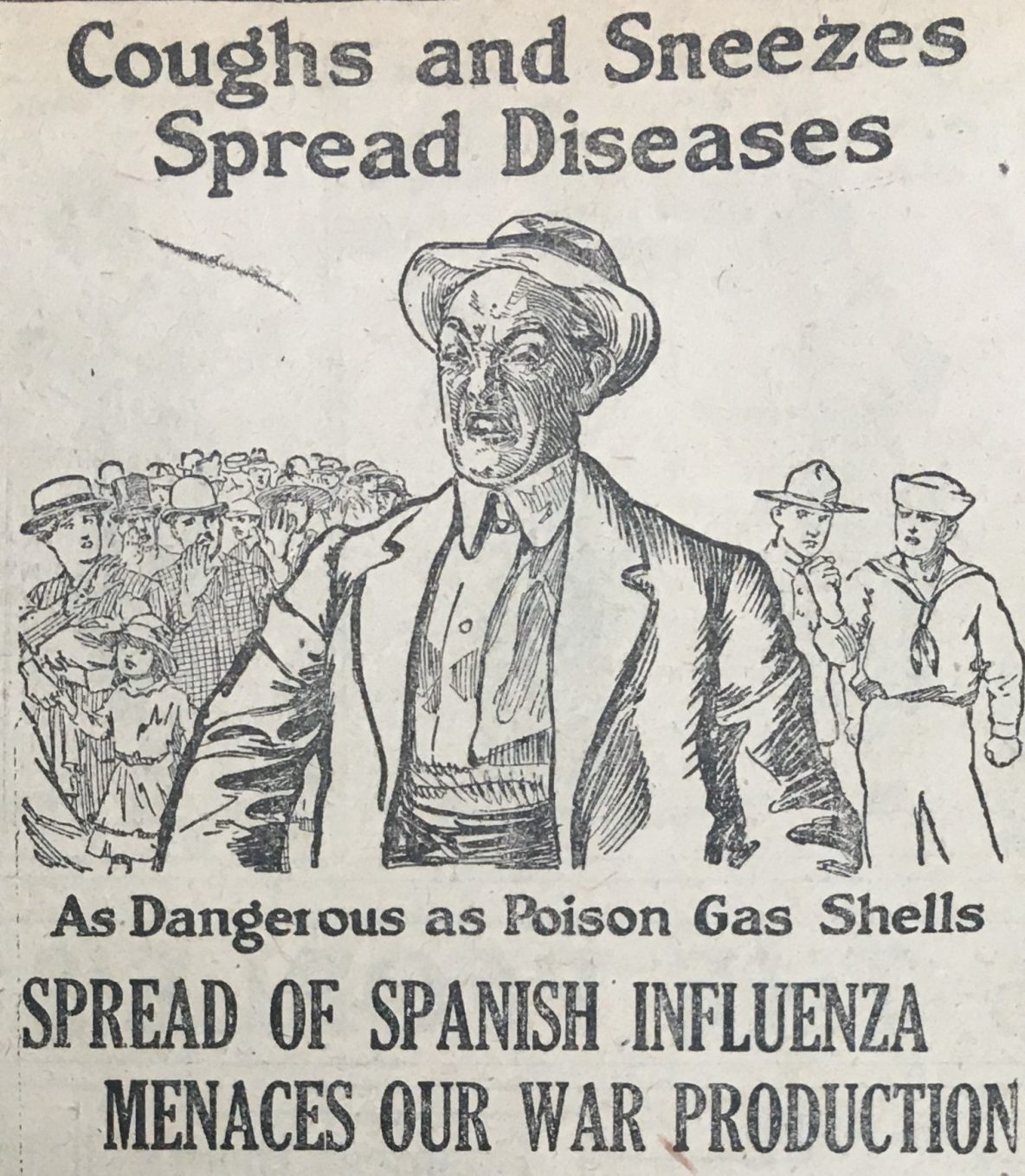

Whittier was only 31 years old when it was hit by the world-wide pandemic called Spanish influenza. It was called the Spanish flu not because it originated in Spain, but because most of the hard-hit European nations were under war-time censorship, so the news just didn’t get out. Spain, being a neutral country during WWI, widely publicized the outbreak occurring there. About 675,000 Americans would die from the Spanish Flu between 1918 and 1920.

The first Whittier death from the Spanish flu occurred at the Whittier State School on September 14, 1918. Cadet Walter Bruhms was a healthy 16 year-old. He caught the flu on Thursday afternoon, it progressed immediately into pneumonia, and he died on Saturday afternoon. Superintendent Nelles personally accompanied the body home to San Francisco. In retrospect, it was not surprising that the State School suffered the first death. The virus (later identified as H1N1 or swine flu) was spread by servicemen visiting or returning home from the war in Europe. The Whittier State School had many former cadets, as well as employees serving the war effort, and many returned to visit. In the 25 days between the first and second Whittier deaths, The Whittier News was full of postings in its “Short News Items of Local Interest” column about servicemen returning from training bases or hospitals to visit their families. This was surely the way the Spanish flu first invaded Whittier. After it got a foot-hold in the City, the virus was transmitted by the now familiar method termed “community spread.”

Although there was a brief respite between the first and second Whittier deaths, the virus was busily spreading in other areas of the Pacific coast – particularly the Seattle area. On Oct. 10, Arthur Hicks, age 18, became the second person in Whittier to die of the Spanish flu.

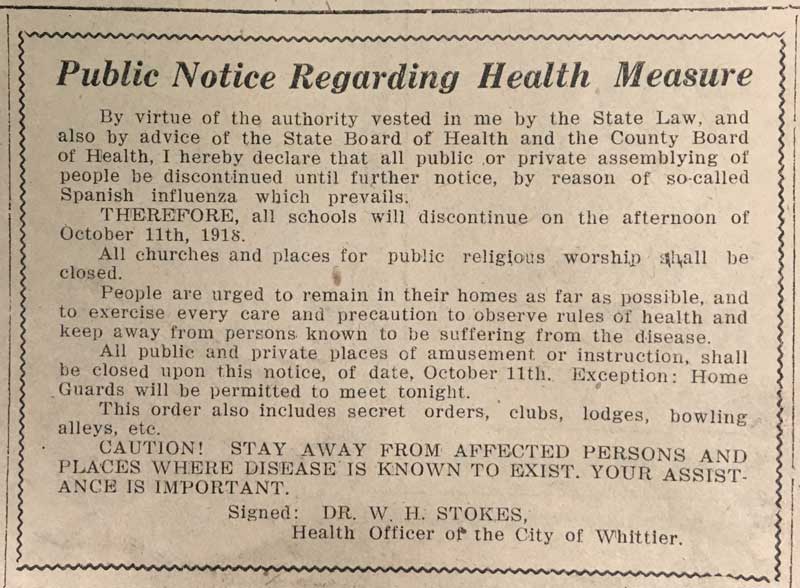

On Oct. 11, the local officials sprang into action. Dr. W.H. Stokes, Health Officer of the City of Whittier, ordered “All public or private assemblying of people be discontinued until further notice, by reason of so-called Spanish influenza.” The order included the closure of all schools, churches, theaters, secret clubs, bowling alleys, etc. Places of employment (besides those specifically mentioned) were not affected.

On Oct. 11, the local officials sprang into action. Dr. W.H. Stokes, Health Officer of the City of Whittier, ordered “All public or private assemblying of people be discontinued until further notice, by reason of so-called Spanish influenza.” The order included the closure of all schools, churches, theaters, secret clubs, bowling alleys, etc. Places of employment (besides those specifically mentioned) were not affected.

Despite the health order, the virus spread rapidly in Whittier. Just a few days later, The Whittier News reported that there were 120 cases of the flu, with about one-third of them being serious. Doctors and nurses were all working very hard to aid their patients. Some of the Whittier physicians became sick with the flu themselves. There was not an emphasis on personal protective equipment in 1918. In fact, the California State Board of Health had to issue an order on Oct. 22 making the use of gauze masks compulsory for doctors and nurses who were treating patients with the flu. Families were urged to be “A little less exacting in their demands for immediate attention as the physician will call just as soon as it is possible.” As with virus treatment today, there was actually little that doctors could do. Fever was treated with aspirin, and if the virus progressed into pneumonia, epinephrine (adrenaline) might be administered. Intravenous treatments were not common at that time, and ventilators were about 10 years in the future. Home remedies, oils, herbs, and dubious concoctions advertised in the newspapers were common. The four drug stores in Whittier worked cooperatively to be open on Sundays with each store taking a three-hour shift. Mrs. O.E. Gregg of 126 North Pickering Ave. offered a recipe for an onion poultice for the cure of pneumonia which she claimed worked wonderfully for her family and neighbors.

Towards the end of October, it was generally thought that the epidemic was waning in Whittier. City Health Officer Dr. Stokes announced that the schools could reopen on Oct. 28, but parents rose up in protest. The school boards voted to keep the schools closed. The Whittier News noted that Halloween was expected to be rather quiet, but “Boys and girls generally stage their Halloween pranks in the open air anyway, so the ban on meetings will not bother them much.” The ban on public and private gatherings was finally lifted on Saturday Nov. 9 at noon; it had lasted for 30 days. The schools also reopened: Whittier College on Nov. 4, East Whittier School on Nov. 6, the grammar schools on Nov. 11, and Whittier High on Nov. 18.

As of Nov. 5, the epidemic’s toll in the local area was: Whittier 564 cases/5 deaths, East Whittier 107 cases/2 deaths, Pico 20 cases/2 deaths, Rivera 62 cases/2 deaths, Los Nietos 35 cases/4 deaths, Santa Fe Springs 20 cases/1 death.

But. It. Was. Not. Over.

On Nov. 18, the Whittier College student body was shocked to learn that fellow student, Donald Story, had passed away after a brief battle with the Spanish flu. By the end of the month, deaths in Whittier had jumped to 20. Mail delivery was spotty because so many mail carriers had the flu. Some cities decided to reinstate bans on gatherings, but Whittier was the first city in Los Angeles County to give quarantines a fair trial. Every dwelling where the flu was present had a white sign posted with the quarantine notice in red lettering. Adults who did not come into direct contact with the patient (usually the father) would be free to come and go from the home. School children who were in a quarantined home had to remain at home for 15 days whether they were sick or not. For those families where children and the mother were ill, the Red Cross would send out a nurse. The number of quarantined homes reached 115 on Dec. 23. The Whittier State School cancelled their annual Christmas festivities and many churches did the same. January of 1919 saw the number of quarantined homes dip to 68 then climb back up to a maximum of 166. After that, a steady decline was seen until, finally, on Feb. 17 there were no quarantined homes. Unfortunately, it appears that the total number of cases and/or deaths was not tracked from December through February (or at least not reported in the newspaper.) Based on the severity of the resurgence in December and January, it is estimated that Whittier must have suffered somewhere between 100 to 200 deaths out of a population of about 7,000.

The Spanish Flu epidemic in Whittier offers us lessons to use in our current COVID-19 crisis. Chief among them is to be careful to keep your containment measures in place long enough. Of course, another way of looking at that is to take care to keep adequate containment measures while not strangling your economy. This is a discussion we’re still having over 100 years later. But whatever you do – if a kindly neighbor offers you an onion poultice, politely decline!

Stay healthy Whittier! We’ll get through this together, just as we did during the Spanish flu.

Author: Tracy Wittman

Originally appeared in the Whittier Museum Gazette, April 2020